Integrating Home Dialysis into Life- old

In our first class, we discussed training to empower patients to be competent and confident at home. In this class, we will cover the transition from the end of training to performing PD or home HD successfully in the home. Moving dialysis into the home is both familiar and new. Supplies are located and arranged differently, for example, and the machine and supplies take up space that was used for another purpose before. There are no training wheels. After a first, observed treatment, when a patient is unsure, you will not be right there to answer questions immediately, though you or an on-call nurse will be a phone call away. The patient is truly accountable for the first time, which is empowering—and terrifying! It is not uncommon to feel a sense of “buyer’s remorse,” regret, or “heaviness” in the beginning. Reassurance is important.

How do you know when a patient is ready to stop training and go home?

- The patient successfully sets up and programs the machine and independently does the pre-treatment tasks (e.g., vitals, weight) in the training bay.

- The patient will start to talk about home dialysis in the future tense, e.g., describing where the machine and supplies will go, or saying, “when I’m home, this will be this way.”

- The patient has passed all of the required clinical competencies.

- You believe the patient will succeed at home.

- The patient self-assesses as being 85% or more sure of the ability to do treatment at home.

Fit Treatment to Lifestyle to Reduce Patient or Care Partner Burden of Care

Ask patients about their daily routines at home without dialysis, to figure out when dialysis can fit into the day or night. Training for home dialysis is not just about how to do the treatments—it’s about when to do them, and where, how long, and how often. Each treatment takes time and energy that would otherwise have been used in another way. Helping patients figure out what treatment schedule will work best for their lives can help reduce the physical and emotional burden of the treatment. As dialysis patients often say, “I dialyze to live, I don’t live to dialyze.”

Consider what prescriptions might work best with a patient’s lifestyle. Imagine that you have a patient whose priority is to have their sleep uninterrupted by treatment—but, he needs longer and more frequent treatments. Where will you put the treatment in his day? Is he a farmer who is up before dawn to do chores.

Or, your patient might be a woman who stays up late at night watching TV? Does she have a job that must be done at a certain time or on a certain schedule? All of these considerations can be taken into account to develop a treatment schedule a patient will accept. So, the farmer might do treatment after supper and then go to bed five or six days a week. The woman staying up late could do treatment while watching TV.

Patients with family or childcare responsibilities will need to avoid school hours, if a child will get off the bus at 3pm, for example. So, they could set up and run treatment after the children leave for school or in the evenings after dinner.

Offer choices and discuss tradeoffs and balances.

Patients do not need to have just one prescription that is done each treatment day. Someone might have time for a 4-hour treatment on Mondays and an 8-hour treatment on Wednesdays. Think in terms of target hours of treatment per week, and no two days in a row off. It’s better to run a shorter treatment than to take two days off. Nocturnal patients who are having trouble at night can do days for a few days. Some patients have separate travel prescriptions for when they are away from home.

Brainstorm which room to dialyze in that will best fit. Talk with the patient, perhaps during the home visit, about which will work. Ask them where they see themselves setting up and running treatments. Some patients think they need to be in a separate room or a bedroom, where they can close the door and forget about it when they are not running a treatment. Others want to relax in the family room watching TV or playing games. Some people are introverts and some are extraverts. Some want to hide their treatment from others and some want to educate them. There is no right or wrong, here.

Have patients with care partners complete a PATH-D again, after training is done and they have seen the tasks that need to be accomplished. This is the time to adjust who will take on which tasks, as needed. Re-using the PATH-D periodically can help provide an early warning about care partner burnout. Include the PATH-D in your Policies and Procedures and document each completed PATH-D in a nursing note in the patient’s medical record with the date and any changes from the last administration.

Schedule a patient’s first treatment at home. If possible, let the patient choose a date to aim for during training. Make an appointment to visit the patient’s home, ideally on a day when you are on call, so your patient will reach you if something happens. If you are not on call that day, alert the on-call nurse that a new patient is starting and may need extra support. That nurse should get report so s/he can be familiar with all of the home patients in the area. Ask the patient to have the machine and supplies ready to go before you arrive. If this isn’t done, wait for the patient to complete these tasks. New patients may want you to do it. Don’t! Say,

“Remember when I told you things will feel different at home, and you might feel hesitant and even regret taking on this responsibility? This is 100% normal. You know what to do! Follow your instructions, go step by step, slow down, acclimate to the environment. For today, I’m here to watch.”

Check the lighting in the room—you may need to pull a lamp from a different room if necessary. Be sure the patient remembers to place emergency supplies, snacks, a charged cell phone, and the TV remote within reach, especially if the patient dialyzes solo.

Watch the treatment until the patient is connected, settled, calm, and looks okay. Then, you can leave, wish the patient a nice treatment and say that you will call in the morning.

For the first 2–4 treatments (or so), do check-in calls and encourage patients to email or leave you notes in the portal letting you know how treatment goes. You might hear things like, “It took me 15 minutes to get my needles in,” or, “It took me 45 minutes to drain, because I was lying down.” Use the frustrations you hear to encourage resilience and trying again in your cheerleader capacity, so patients feel supported and are not afraid to try again.

Monitor the home patient. As a nurse, you need to forensically examine the flowsheets for anything that will cause stress. Look at the number of treatments, patterns, and pressures or alarms.

Call patients about anything that looks like stress on a flowsheet; they don’t yet know what to look for

What to look for in the flowsheet trends

Call patients and explain the rationale behind what you find and why it is a concern. For example, “I noticed that your venous pressures have been running 20 points higher at each treatment. Are you having trouble placing the needle? Has anything changed about your access? Is it bleeding longer after treatment? Listen to your fistula. If it sounds like a high-pitched whistle, you may have stenosis (a narrow spot) and need to see your vascular surgeon.” Empower patients with knowledge, so they can point to the spot where the stenosis is.

To pay attention to their baseline vital signs and let you know if something changes

They should let you know when something (like their blood pressures) is running higher or lower. Call the patient when lab test results come in—even if nothing is out of the ordinary, if there is no portal. Remind them of the lab process in the first couple of months when it is new to them. Ask if they have any questions and have the instructions. When they come in, go over the labs point by point and explain what they mean and why they are important. This repetition is how patients learn.

To inform the home program of any recent procedures, imaging, hospitalizations, or lab-work done outside of dialysis

Obtain the records—especially labs not typically drawn in dialysis that can help guide care (ie—BNP). Document outside findings in case anything is needed for justification or continuity of care. Have patients tell you ahead of appointments so relevant information from dialysis can be sent in reciprocity. Have all consults, discharge plans, reconciled medications and results of labs/tests available for review at clinic visits.

Call your patients on their birthdays. These matter to your patients! You will also need to respond to calls and questions and offer resources, such as support groups.

Get the Most Out of Clinic Visits

Patients need to obtain value from clinic visits and to feel that they are being actively monitored and cared for. No one likes to have their time wasted, and we don’t want home patients to feel abandoned. Get your ducks in a row before the visit. Show that you value the time spent face-to-face with your patients and any care partners who can attend.

The first time a patient comes in for a clinic visit after starting treatment at home, do the look test. How does the patient look today? Do you notice a difference in their appearance or energy or skin tone? How is the patient’s hygiene?

Did s/he dress up for clinic or dress in a way that shows their personality? (That’s a good sign). It’s fine to comment if a patient has started to look better. If a patient doesn’t look okay—is very short of breath, for example, or their color is off, ask about that, too. Observe/ask about the patient’s frame of mind, mood, level of pain, distraction, etc.

Ask the patient and care partner (if present) how the treatments have been going. You might ask, “What don’t you want to tell me about? Have you had any mishaps or errors?”) “Are you using your checklists?” Don’t judge or blame. Even if a patient tells you something that is clinically unsafe, use your poker face, and unpack it: “Thank you for telling me. Learning this helps me keep you and other patients safe.” No nurse has seen everything. Patients seem to be able to find new and exciting ways to make mistakes, and you can learn from those and prevent them in others. So, we don’t want to make our patients afraid to tell us. We need to hear about these mistakes.

Assess patient attitudes and help them to reframe if necessary.

You’ll also go over the lab test results and explain them, do a proper cardiac and lung assessment with a stethoscope, and take a manual blood pressure. Good labs usually happen when patients report feeling well and are comfortable with treatment. Check out the access and/or PD catheter, and keep an eye on fistulas in PD patients as well as HD patients, as they may develop aneurysms, thrombosis, stenosis. Talk with the patient and determine if the prescription is working out or needs changes. Provide written instructions for any changes to the plan. Provide written instructions for any changes to the plan.

For subsequent clinic visits, call patients before they come in, so you know what to advocate for. Ask patients:

- “What do YOU want out of this clinic visit?”

- “What do you want to talk to your doctor about?”

- “Do you need help?”

In addition to all of the steps from the first clinic visits, you will want to start to review monthly clinic and water expectations with materials so patients can do this solo and bring in the results. This is like starting to remove training wheels; turning over ownership of these steps to the patient. “I don’t need to remind you. You know which day to place your order. You know to rotate your stock…”

Consider whether antihypertensives and binders can be deprescribed (oh, happy day!)

Conclusion: Getting to One Year

Conduct pre-visit calls with patients about their labs, medications, and concerns. Encourage the patient and care partner (if there is one) to take back activities they enjoyed before ESKD, like travel, or start new ones they’ve always wanted to try. Ahead of the visit, share any concerns about a patient with the nephrologist.

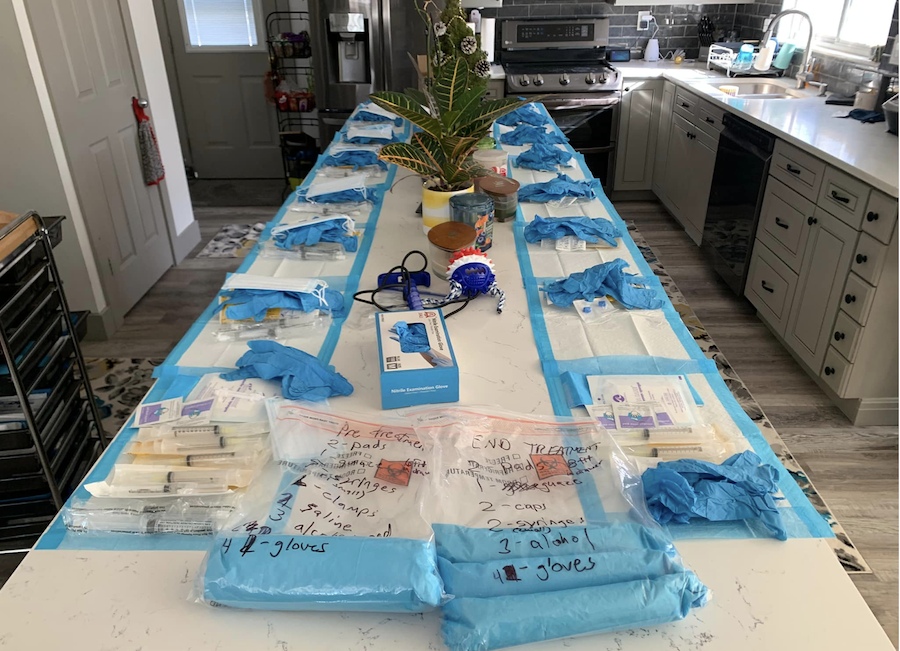

Assess the therapy burden. Ask patients how they feel about the time treatments take, supplies, etc. Ask if they can suggest some ways to reduce their burdens. (E.g., making supply packs. Share those suggestions with other patients. A good sign to watch for is if a patient’s primary complaint is something other than dialysis—like how much they hate their granddaughter’s new boyfriend!

Remember that the patient’s motivation impacts success at home. For example, we need patients to fill out treatment sheets—which many hate to do. Explain what’s in it for them. You might share that you look at these to see if they are having frequent alarms or interruptions you can address so their treatments run more smoothly. Home HD patients may resist the need to take monthly water samples and check chloramines. Show them what happens when blood comes into contact with chlorine. Use a syringe to drop a bleach mixture on top of blood, so they can see the hemolysis. Involve and teach patients to help them own the treatments they do.