Training for Home Dialysis Success – old

Learning Objectives

Support competent, confident patients. Before you even start training, think about what the goal is. It’s not just to teach someone how to use a machine, step-by-step. The goal is to empower patients to understand their treatments, their symptoms, the relationship between their treatments and their symptoms—and what to do and who to call if something goes wrong. The goal is competent, confident patients who can self-manage and troubleshoot. This means—and research supports (Wise M et al)—that patients do best when they can be as independent as possible with their treatments. Solo patients are, of course, the most independent of all.

Motivation comes before learning. Patients need to know WHY they are there. Rationales are critical for adult learning. Adults will not just do what you tell them to do without a reason that affects them. They don’t want to hear, “Because that’s our policy.” Self-managing patients need to understand what they need to do and why it is in their best interests to do it.

Ask about the patient’s short-term and long-term life goals (5-Bieber 2021). Find out what matters to your patients and use that information to frame your teaching. For example, a patient may be highly motivated to go ballroom dancing. So, you can frame everything you teach in terms of “Slowing down the ultrafiltration rate will help you have the energy you need to dance, even if it means the treatment runs a bit longer.” “More dialysis can help you sleep better, so you are well-rested for dancing,” etc. Teach patients to be grateful for the machine self-checks, even if they add a bit of time.

Ensure that a patient wants to do PD or home HD and knows why. To get someone to do a job (like PD or home HD), you explain what the job entails and s/he has to want to do the job. It is not enough for a doctor or a favorite nurse to tell someone, “You would be so great on PD,” or, “You should do home hemo.” Patients need to own the decision and do it.

Trade-offs, in particular, are sometimes glossed over in favor of unvarnished enthusiasm that may not serve patients well. You may be able to offer an in-center trial of a home therapy, such as Experience the Difference. If patients are contemplating CAPD, you can suggest that they stop what they’re doing four times a day and watch the clock for 30 minutes to try on the therapy.

When home HD patient trainees have care partners, check any impulse to turn the partners into dialysis technicians. To the extent possible—which varies—encourage patients to take ownership of their treatments and do as many of the tasks as possible. Care partners ideally should not be required to attend all of the training sessions. To minimize the risk of care partners using up all their annual leave for a year when a patient can learn and do the treatments, invite a care partner who has never seen dialysis to the first day of training and the last 2 or 3 days to learn when to call 911 and how to stop the blood pump in an emergency. If a care partner wants to come in on a day off, have the patient teach the partner—which reinforces your teaching and that the patient is in charge.

Patients and care partners who are retirees may want to come together as something to do. If so, keep the partners busy. Teach them things like how to order supplies, do inventory, or read the HD or PD machine manual and tell the patient exciting things in it. Teach them how to make supply packs. You can set up a secondary, practice machine and have care partners try to set up and take down.

Position patients for success by teaching them practical skills. For nurses, this is in muscle memory. Patients need to learn this, too, and be confident about it. This confidence spills over into other tasks. Test HD patients’ color vision at the start of training, as the ability to distinguish between red and blue is vital for safety.

Patients need to differentiate when to call the nurse vs. the manufacturer for PD or home HD problems.

Urgent RN

- Access function issue (infiltration, blood loss > 275 mL, high pressures, weak thrill, bleeding, CVC or PD catheter dysfunction, trouble cannulating)

- Change from baseline vitals

- PD contamination

- Possible infection/reaction

- Confusing machine alarms

- Treatment or equipment safety Qs

- After an emergency that required 911 or EMS

Routine Home RN

- Hospital, blood work, ER/MD visits, EKGs, imaging, falls, infection, prolonged bleeding, emergency ends HHD/PD early, life change

- Problems prevent finishing PD/HHD two or more times

- Symptoms (fever, SOB, infection), consult on TW…

- Vascular access Qs

- Travel plans and orders

- Clarify the care plan

- Supply concerns/needs

- Submit labs, med refills, water samples

- Adjust PD treatment

- Explain non-routine calls to on-call RN, vendor/courier, damaged supplies

- Do a machine swap

- Qs: nephrologist/care team

Manufacturer/Vendor

- Alarms during HD won’t clear or keep coming on

- Weight discrepancies or calibration concerns

- Settings questions (Qs)

- Routine maintenance Qs

- Before a supply shortage becomes a crisis

- IT issues with connected health, etc.

- Suspect vendor defects. Take photos, tell clinic & FDA device watch

Patients also need to learn how to recognize symptoms and relate them to treatment (self-assessment). Download our handout “Whom to Call and When” to help patients differentiate when to call the nurse vs. the manufacturer for problems.

Teach Clinical Process Thinking

To help patients learn how to troubleshoot, we can teach them the type of clinical process thinking that we use ourselves. Nurses are trained to prioritize everything we do and understand what is a potential problem, even if it doesn’t seem like one.

Stories are Powerful

Telling patients about a worst-case home dialysis scenario may help them avoid it. For example, there are two ways to rinse blood back on some machines. One is to close the arterial bloodline and infuse saline. The other is to disconnect the arterial bloodline from the access and move it to the saline port. But, a patient who accidentally moves the venous line can divert the entire blood supply to the saline bag—which can be fatal. Tell patients, “This has happened before and will happen again. You don’t want it to happen to YOU—always check the colors.”

Teach patients how to respond to this error if it happens:

- Stop the blood pump.

- Disconnect the lines and reconnect them correctly.

- Rinse back the blood that is in the system.

- If a significant amount of blood was infused into the saline bag, that needs to be reinfused, too.

For HD, they need to know that red is always pulling and blue is always pushing. They need to understand the extracorporeal circuit. PD patients need to be alert to sudden pain and shortness of breath that might mean overfilling.

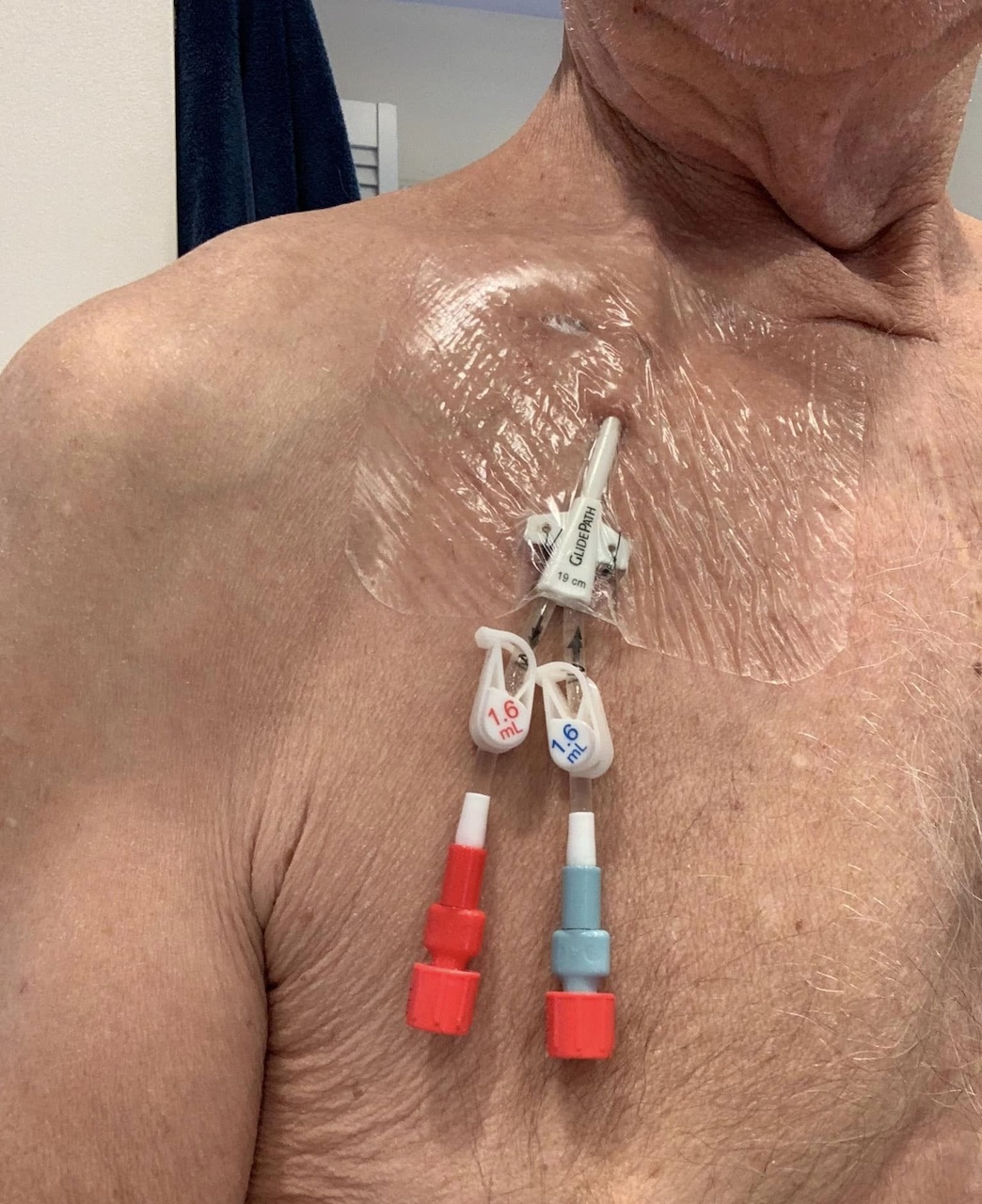

Access issues can be an important factor in home therapy failure. A good working access is important everywhere, and especially at home, because home patients with difficult accesses will be trying to manage by themselves. You would never put a beginner tech on a difficult fistula. Patients who start with an access that is problematic for a nurse will be at a major disadvantage, and their confidence about PD or home HD can be damaged. Everyone who works with home patients needs to understand this. Rally the nephrologist to advocate with the vascular surgeon or the surgeon who places PD catheters. Doctors work with the groups they are affiliated with. Because of that, in some places, a physician group may or may not have a surgeon who is experienced with access surgeries. It can be very challenging for the nephrologist to explain why a patient should see a surgeon outside of the preferred group. But, patients deserve to be able to see a surgeon who can get them a working access.

Befriend or become an access coordinator to advocate FOR home therapies and liase with surgeons.

Prioritize access planning, self-cannulation (HHD), and patient independence. When you have the opportunity to talk with your patients before they go for a surgical consult for a PD catheter or an HD access, teach them how to advocate for themselves and what to ask for. For example, make sure the surgeon observes them sitting, standing, and lying down before deciding where to put a PD catheter.

Patients should tell the surgeon which their most important hand is—if they play guitar, for example, it may not be the hand they write with. Make sure the patient can reach a fistula or graft to self-cannulate. Large breasts can get in the way, or an access on the back of the upper arm requires a care partner for cannulation. Fistulas and grafts should not be placed in the axilla.

In a perfect world, prospective home HD patients learn to self-cannulate before they start training, in-center or in a transitional care unit. Self-cannulation is a bridge to home HD. (Lockridge R et al. 2020) Since there is so much angst around the needles, and needle fear is prevalent in 1/3 or more of patients (Shanahan L et al. 2019), helping patients overcome needle fear and succeed at self-cannulation may help improve home HD retention. Anecdotally, knowing how to self-cannulate has shortened training time, sometimes by 2-3 weeks.

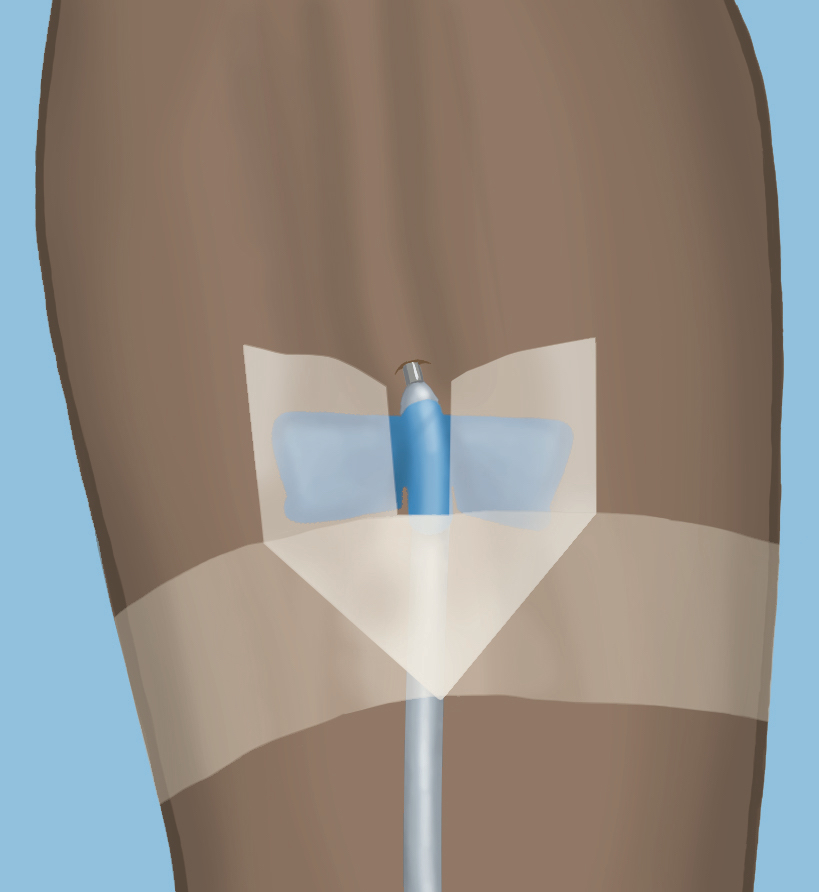

Since we don’t live in a perfect world, chances are we will need to teach our able patients (those who can see and use their cannulation hands) how to self-cannulate and tape safely to prevent needle dislodgment. Each patient is the only one on earth who can feel both ends of the needle. Tell your patients this before you start—it helps to boost their confidence. Encourage the patient to feel their access from one end to the other on the outside and feel it internally for position. Touch it, roll it, learn it. We want them to learn the bends and twists and rolls it may have. Have the patient keep the other hand on the fistula or graft and supinate and pronate their hand, so they can learn the relationship of the vessel to the bone. Then, they can hold their hand in the position that gives them the longest straight stretch to aim for. Often, this is thumb’s up. For Buttonhole cannulation, they need to memorize that hand position, since the hand position and needle angle need to be the same. You also need to understand each patient’s access from his or her perspective, facing the same way as the patient.

Give a patient a capped needle and ask where s/he would place the needles. This can help desensitize a patient to the cannulation motion that will be used, and if Buttonholes are a good choice, will help identify the best Buttonhole sites.

Teach patients what you are doing each time you cannulate: how and why to wash the arm, the angle of needle entry, leveling off. To help patients overcome severe needle phobia, it may help to take pictures of the access and the needles to hang on the refrigerator for a few days. The next visual can be an access with a needle taped down. Encourage hesitant patients to go on Amazon, look up quick release tourniquets (with buckles), and pick one they like. A patient who buys a tourniquet and brings it in will self-cannulate.

You may want to give needle phobic a blunt needle to touch and play with, tape down to a clipboard, tape to themselves, etc., to get used to holding the needles. Alert patients to the first cannulation day (“Monday, you’re going to do the arterial.”) Set up the machine for patients that day as a pleasant surprise, stay calm, and don’t make cannulation seem like a big deal. Show them this 5-minute video of children self-cannulating to inspire them to try.

- Two hours before treatment, wash the access with soap and water to remove skin oils, and dry gently.

- Apply two dime-sized blobs of EMLA 1/8” thick over the next cannulation sites. This requires knowing the cannulation pattern for the rope ladder technique.

- Cover the EMLA with plastic wrap or a Tegaderm™ or other waterproof dressing to hold in heat to help the EMLA penetrate the skin and to keep the cream off of clothing.

- Just before treatment, wash the EMLA off. It may temporarily blanche the skin a bit.

Apply a piece of anchor tape for patients just for this treatment. Then, be a second set of hands for taping. Show how to plunge the syringe to check the flow and patency, clamp and flush with saline so the line doesn’t clot, and help them complete the taping the first time or two, which needs to either use a chevron or butterfly technique, as engineering research finds that these two techniques that wrap the tape around the tubing are far less likely to allow a venous needle dislodgement (Chan DYF, 2020). Practice taping needles on yourself, so you can show patients how to do the techniques one-handed. Once the needle is flushed and taped down, it’s safe, and you can congratulate the patient, share the news with other staff, and make a big deal out of the accomplishment!

If the arterial needle went well, ask if the patient wants to do the venous. If not, you do it that day and the patient will do it for the next treatment. Help patients make the line connections that day, too.

Determine what can be used in training to give the patient an attainable goal (and then another goal, and another…).

Adults learn what they want to learn, because it is relevant and they want to learn it: always provide a rationale. Ask what people know before you try to teach them anything.

Find out about each patient’s background, so you can use relevant analogies (e.g., a fishtank, car, or swimming pool to explain dialysis filtration) and idioms “What goes in must come out,” “What goes up must come down…” “What goes around comes around.”

Tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Use plain language, not jargon. Add medical terms later as understanding improves. Keep materials at a 5-6th grade reading level with pictures.

For really important points, come up with a quick pop-quiz that you can do out of the blue.

Repetition, repetition, repetition… is a key principle of adult learning. We have been using it with you in these classes!

Be a cheerleader: offer additional training and support as needed. (1- Tran 2023) Patients report fear and stress around machine alarms, complications, routine responsibilities, and catastrophic events like SCA or exsanguination.

Go through the machine manual with the patient. Talk about how the machine works, so they are less afraid of the alarms.

Share errors other patients have made that caused bleeds (e.g., poor taping), so they can avoid making the same mistake.

Review basic first aid and health care—what to do about bleeding, signs and symptoms for heart attack, stroke, sepsis.

Desensitize patients to alarms by causing alarms—and letting them practice handling them.

Frame home treatment in a context that is relatable to the patient to reduce fear and facilitate learning. E.g., if patient has experience plumbing or following recipes—use that as an analogy to make it seem at least somewhat familiar

Observe the power dynamic between a couple, so you don’t impact it in a negative way. (1- Tran 2003) For example, don’t enable an able patient’s dependence on a care partner. If a patient and care partner squabble continuously, you may need to train the patient for solo and keep the care partner out of the training process.

Step in to support a patient’s ownership of the disease.

Encourage the patient to support a partner maintaining social activities. Point out the importance of showing appreciation: giving hugs, saying thank you, planning dates, and making eye contact….

Be open to discussing intimacy, especially if that’s a motivating factor for a patient doing home dialysis. Ask “Is your disease affecting your sex life in a way that makes you unhappy?”

Conclusion

Your goal for PD and home HD training is to empower competent, confident patients. Your patient’s goal is to be able to keep what matters to them in their lives and feel safe, competent, and confident. Helping patients to “own” their treatment and master the necessary skills gives them back control of their lives that many had lost when they initiated dialysis. Part of your task is to find—or become—a champion for PD or home HD access for the patients you train and to become confident yourself in teaching patients how to use their accesses safely and successfully. Finally, helping your patients set or reach a successive series of small goals, using Adult Learning Principles, and strengthening relationships between your patients and their partners (if they have one) will boost the chances that your patients will go home and stay home