Setting Staff Expectations about Home Dialysis old

Be mindful of your first impressions, because we all come to situations with a lifetime worth of background about culture and people that can be hard to shake. Culture is the water we swim in and the air we breathe—it can be difficult for us to challenge our own assumptions and give people the benefit of the doubt. Biases come from generalizations, and interacting with individuals can help us to prove them wrong. Have conversations with people who are not the same as you and look for commonalities between you. Treat every patient with respect. As an NIH blog post says, “Your belief in the inherent worth and dignity of all people influences positive change.” (NIH blog, 2023)

Adjust your perceptions and get to know your patients as individuals. Start by walking into your workplace as if it was the first time. Look around. Think about it. Your patients are terrified, sick, and overwhelmed. None of them want to be there. From the parking lot to the home treatment training room, garbage, desk clutter, squabbles between staff, etc. reduce confidence in you and the training program. Whatever you can do to improve the environment to make it clear that they are cared for by people who care changes their attitude and demeanor.

Give patients a chance to surprise you! It’s not uncommon for us to underestimate what in-center patients can do at home, especially when we typically see them at their physical and emotional low points. They may come in wearing pajamas with their hair uncombed. They may snap at us—or ignore us completely. They may be angry at the universe—and we might feel exactly the same way if we were in their shoes.

Yet, they may have really nicely kept homes. They may have had rewarding careers before they were derailed by kidney failure, and may still have ambitions for things they want to do. Home treatments can give patients back their lives, if we give them a chance. Find out what their motivation is—and don’t underestimate what motivated patients can do!

What does a home patient look like?

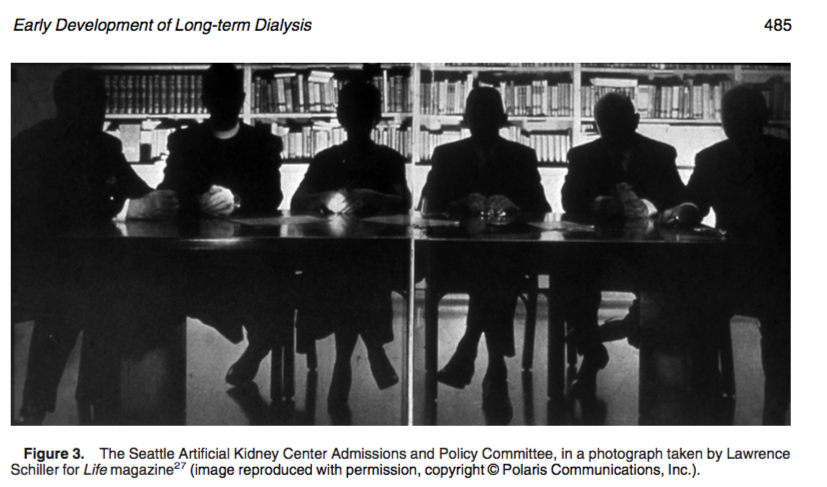

What should a home patient look like? Sometimes we unconsciously have an image in our heads of the “perfect” home patient. Examine your assumptions. If they lean toward white, middle class, men married to nurses, you are not alone—these were exactly the patients who were chosen for dialysis in the 1960s when treatment was rationed due to cost.

“Non-compliant” Patients

If patients are not showing up for in-center treatments or are disruptive, they may be highly motivated because that modality is a poor fit for them. These patients may be very firm about their ultrafiltration goal. They may insist on a certain person cannulating them or a particular chair. Patients who express their need to control things can be excellent home patients—because they get their control back

Patients Who Appear Eccentric or Quirky

Don’t look at patients and rule them out solely on the basis of appearance.

Avoid a Checklist Mentality for Patient Selection

Checklists can be wonderful tools for assuring that steps are followed in order or a suitcase contains what will be needed for a trip. Dogmatic programs that select patients based on preconceived “ideal” visions do not tend to grow. Joan Lunden famously said “People have to want something more than they are afraid of it.” Home dialysis is scary to most patients who are just learning about it. Helping them to find their motivation is key. Motivated people will climb mountains to get what they want. Home dialysis is their path up the mountain. Stay with us and we’ll talk about how to determine your patients’ motivation. (5- Bieber 2023)

Consider Your Patient’s Emotional State and Learning Readiness

Patients who are fearful cannot learn. (Video V1.1.6 – DS – Fear; fear vs. hope). Patients deserve to know that they can’t learn when they are afraid. HOPE is the flip side of fear/anxiety (Hammer K et al, 2009).

Hamlet said, “The readiness is all”. We often forget that there is a step that comes before learning: readiness. People are not ready to learn until their minds are calm. When we acknowledge and address their emotions, we can help get them to a place where learning becomes possible. We can start by saying something like: “You are feeling grief and trauma and fear. That is 100% normal for your situation—if you didn’t feel this way, I would worry about you. You can get through this, and I am here to help.” Keep in mind that patients don’t always know what they’re feeling.

Pay attention to your body language—and the patient’s and care partner’s (if one is present). Make sure your posture is open when working with your patients and watch their postures too.

- Look people in the eye.

- Sit down to talk to patients.

- Don’t cross your arms in front of your chest or back out of the room.

- Wait for patients to feel comfortable with you: watch for relaxed shoulders and signs of personality—people feeling free to be themselves with you.

Open Posture

Closed Posture

You WILL likely be asked “How long do I have to live?” The answer is “Nobody knows. At any given moment, anything can happen to anybody. The only thing we can do to improve your chances is to do treatment in a physiological way.”

Ask open-ended questions to get acquainted and check on patient status. For example, you might say, “Tell me about yourself. What do you like to do?” and give the patient a chance to answer. Follow up with “What do you want to be able to do?”, “What matters most to you right now?”, or “Where would you like to be in a year?”

You can offer a Life Options free Goal-setting Worksheet to patients who need some help clarifying their goals. These worksheets give you clues to the patient’s motivation.

Explain to patients that uremia is a barrier to learning. Symptoms of uremia like brain fog, forgetfulness, and lack of focus make learning difficult. Better treatment delivered during the training process may help some physical cognitive issues. Just being aware that these are physical symptoms and not lack of intelligence can help. Reassure them that they are not going crazy. Ask what they know about uremia; describe symptoms/causes if they don’t know.

Consider diagnosed—or undiagnosed—illiteracy. In the U.S., the National Center for Education Statistics estimates that 21% of U.S. adults (43 million) do not have the literacy skills to compare and contrast information or state the meaning of a paragraph. Patients with functional illiteracy are ashamed and can be very good at hiding their inability to read. They may “forget” their reading glasses, hold pages upside down, not look at the words on a page. When you ask them, “Can you read?” they may admit that they can’t. Once you know, you can adapt training materials to use pictures, videos, and mnemonics to help them remember. The social worker may be able to refer patients for literacy help if they are interested.

Overcome Challenges to Home Dialysis Success

Provide useful information to help patients make informed choices. Don’t oversell benefits of home therapies: be realistic about tradeoffs.

Patients are concerned about how home treatment can fit into busy daily schedules, educational obligations, social engagements, and hobbies (8- Jacquet 2019).

Nocturnal PD and HHD can cause sleep disturbances, especially when there are machine alarms or frequent issues (3- Jacquet 2019).

There is no “easy” way; the only “good” choice is one the patient chooses. Complete a MATCH-D to assess patient suitability for PD or home HD, then guide patient candidate for home therapies to My Kidney Life Plan, the non-profit Medical Education Institute’s free, online decision aid, written at a 5th grade reading level in English and Spanish.

Adults learn if they have a goal and believe what they are learning is relevant to it. Continue to frame conversations with patients around their goals.

What matters most to patients is how treatment will affect their quality of life. A number of studies have found that patient priorities tend to be very different than what clinicians think their priorities are. Clinicians may tend to focus on “objective” measures such as Kt/V or lab test values (3-Jacquet 2019). Patient priorities tend to include:

- Fatigue

- Coping

- Travel

- Impact on family

- Employment

- Sleep

Identify patients at high risk of training and/or early home dialysis dropout and develop strategies to address challenges. Ask if they are having physical issues:

A non-working access for PD or HHD puts patients at risk of dropout.

Recent falls or medical setbacks such as a stroke or tremor can affect patient confidence, belief in their ability, and health status.

Treatment side effects that cannot be managed, such as PD drain pain or idiopathic intracranial hypertension can reduce motivation to continue with a home therapy. The perceived benefits of a home therapy need to outweigh the downsides.

Are the patient and/or partner getting along?

Do they treat each other well? In general, it’s ideal to have the patient own the disease and treatment and do as much of the home therapy as possible. We don’t want to foster co-dependence, turn a care partner into a dialysis technician for an able patient, or make an interpersonal issue between a patient and a care partner worse. If you notice static between a patient and a potential care partner, the friction when they go home can cause so much resentment and anger that the relationship and the home therapy can fall apart, which is devastating. It may be better to train the patient solo, and train the partner only for emergency management. Ideally, the care partner’s role is the “Hey, honey, can you bring me a ___”.

Observe the patient for lack of engagement in training or care.

Patients who are not engaging may not be motivated or they are not seeing the big picture at the end. Something else may be going on that is preventing them from learning what they need to do to get there. Patients with failed transplants may not be ready to go home—yet—but, may get there in time. Keep them close to the home program and be inviting. Others may be partially trained and need a break before they can fully commit. Doing in-center for a while may help them clarify their motivation. Keep them on a check-in list, along with patients who are friends with your home patients. You can call patients out for being unfair to a care partner, for example refusing to agree on a treatment schedule, which holds the partner’s time hostage. Some tough love can be helpful, and the patient may even respect you more for it. Encourage care partners to support patients being as independent as they can be.

Introduce patients to others on home dialysis to help alleviate stress.

Consider referring patients to support groups, in person or online. HIPAA keeps you from introducing patients to each other, but you can schedule similarly-minded patients to clinic visits at the same time, so they can meet in the lobby. Tell patients that you do this sometimes, “I schedule patients so they might run into someone who has something in common with them.” Group training is another way to accomplish built-in support for patients and care partners.

Home Dialysis Central offers a moderated Facebook discussion group with more than 7,800 members. You can also order free postcards to share home dialysis resources with your patients.

Treat Your Patients Like the Adult Learners They Are

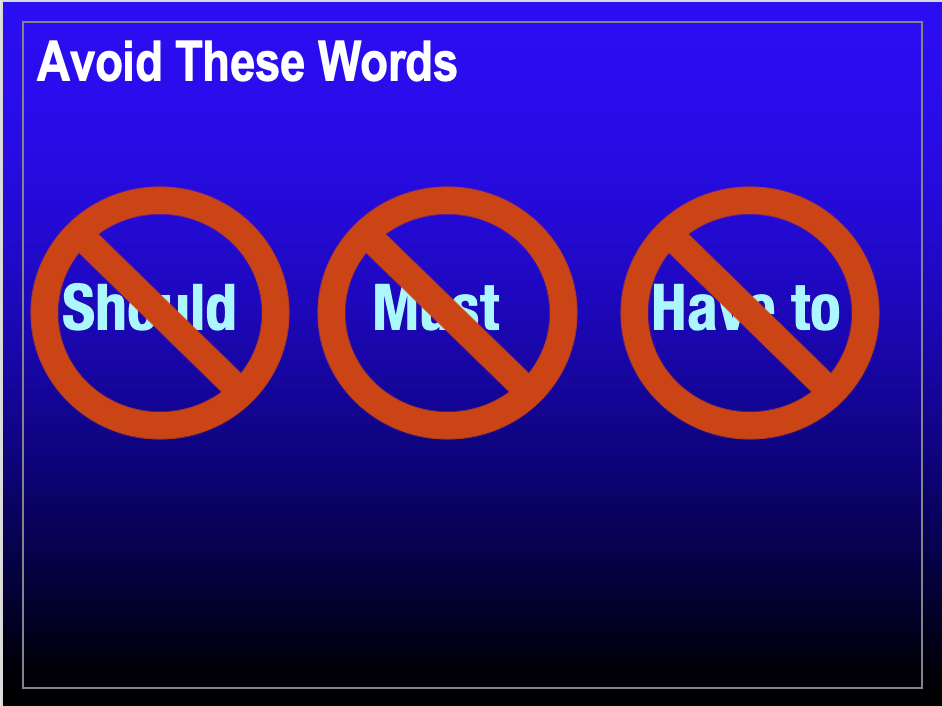

Adult learners tend to react badly to being told what they should or have to do.

These words are triggering and can cause resistance, so they are best avoided. If you have parents or children, you may have seen this in your own life. Instead:

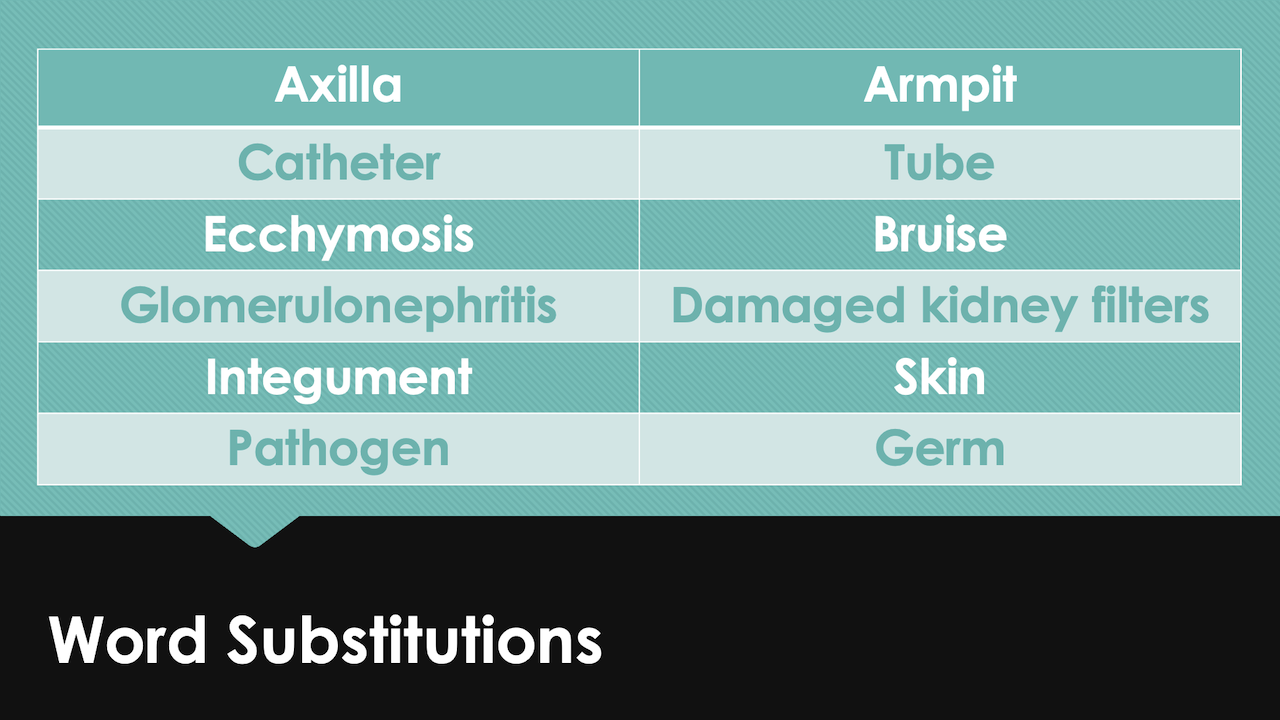

Provide information in a way patients understand.

Medical terminology is unfamiliar or too complex for some patients. Use lay alternatives where possible (6-Cho 2023)—at first. Many home dialysis patients feel unprepared at first, due to a lack of formal education (1-Tran 2023). They need to learn and understand the correct medical terminology to express their thoughts accurately to their health care providers—who may be very literal about medical terms.

Education cannot be one-size-fits-all, even if a curriculum is standardized. Focus on each patient’s priorities and concerns to adapt the tone and topics and provide individualized education that “sticks”.

A number of patients want to be able to play with their kids or grandkids. You can tell them that trying to do treatment this way or that way may let them…play ball with their kids. Tie back to their motivation, always. Motivation is the hook. (3-Jacquet 2019). Your approaches will differ for each patient—this is person-centered care.

Provide Autonomy Support

When patients feel better—and sense that YOU BELIEVE IN THEM, they produce better health outcomes for themselves (Williams GC et al, 1998).

Help build confidence. Your confident attitude drives your patients’ attitudes. This is key for patients to choose home dialysis in the first place. They have to believe they can do it—and that YOU believe they can succeed. They will want to please you and make you proud of them, which gives you the power to reward them with positive attention. Keep your overall tone positive—not critical. Video V1.1.5- JR – contaminating catheter)

The model of care in-center is very different from what we aim to do at home (rightly or wrongly). In-center, we provide care to groups of mostly-passive patients. These patients—all patients—have the CMS-protected right to be as involved in their care as they want to be, including self-cannulation, which does not require a separate certification.

At home, our task is to empower our patients to take excellent care of themselves; perhaps with a care partner, perhaps solo.

This is a completely different approach. What we need to do is align each patient’s goals with the truth about home dialysis: it takes an investment in time to learn and set up and do a home therapy, but once patients are proficient and get into a routine, they will benefit from more energy, fewer dietary and fluid limits, more control over their schedule…better quality of life overall, and likely better survival as well.

Not every training nurse is a good fit for every patient! If you feel like you have started out on the wrong foot with a patient, or there is a personality clash that can’t be reconciled, it takes humility to recognize that you may not be the best training nurse for that person. If you have a patient you are not connecting with who is having difficulties with training and is at risk of dropping out, it may make sense to trade. Sometimes bringing in a colleague might salvage the situation.

Conclusion

Your expectations of home dialysis drive the success of your home program. When you treat patients respectfully as unique individuals, you improve the chance of building rapport that will lead to effective training and empowered, competent, confident patients. Consider readiness prior to any educational efforts—fearful patients cannot learn. Offer hope with goal-setting, stories, a buddy system, praise for forward progress, etc. Learn your patients’ motivation and use it to frame your teaching. Be realistic about the tradeoffs involved in home therapies and identify patients who are at risk for early dropout. Keep in mind that your patients are adult learners who need rationales for tasks and simple language first, before you introduce more complex medical terms. Finally, when your patients believe that YOU believe in them, they are more likely to succeed.