Setting Patient Expectations for Home Dialysis old

Step 1: Aim for a Good Fit

A treatment option for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is more than just a way to clean the blood—it is a new lifestyle. While there are no studies on this topic, it is easy to surmise that the best chance of maintaining a patient at home on PD or home HD is to make sure that the choice of treatment is a good fit for the patient’s values. Patients who have never done dialysis are unlikely to know what their best fit is. Staff who don’t know the patient’s values are also challenged to help patients make a choice that fits their lives.

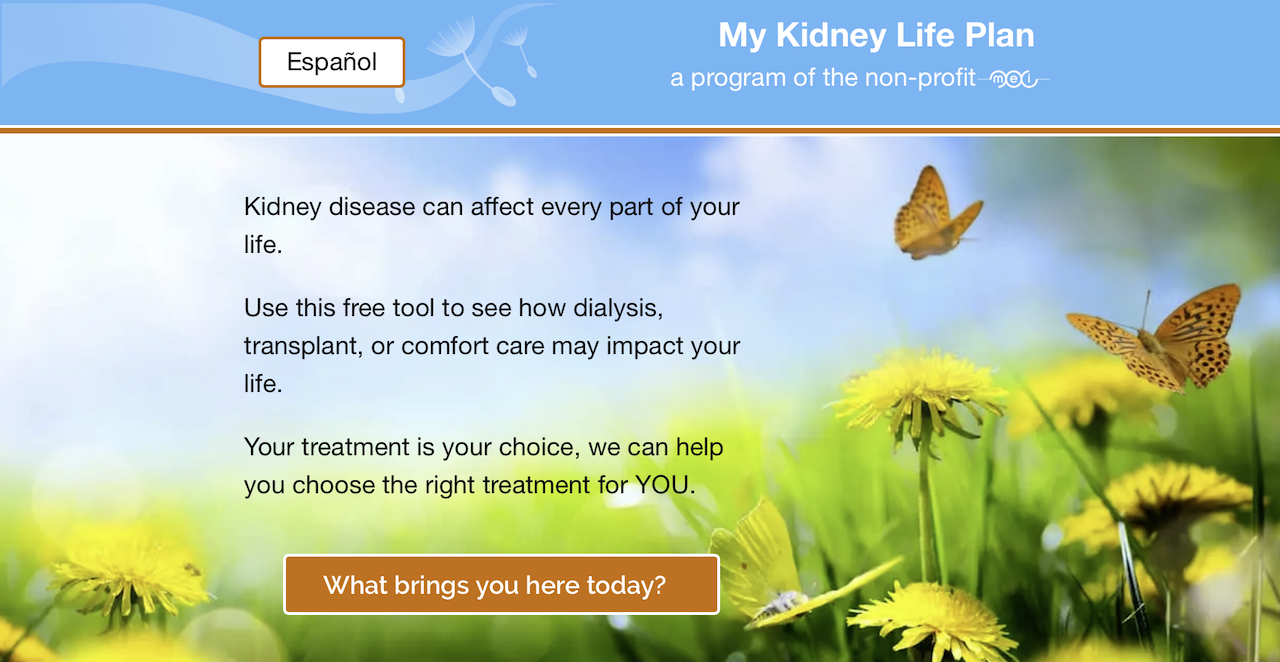

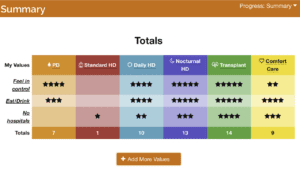

The non-profit Medical Education Institute’s evidence-based decision aid, My Kidney Life Plan (MKLP) helps to bridge this gap. Written at a 5th grade reading level in English and Spanish, MKLP covers all of the treatment options for ESKD: transplant, dialysis, and active medical management. The tool meets all of the criteria of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS).

The one-page summary of the patient’s values and modality ratings serves as an Advance Directive for modality choice and helps clinicians hold a shared-decision-making conversation with patients. Used first, MKLP offers patients critical hope, helps them clarify their values, and establishes their motivation—which facilitates learning.

Step 2: Clinician Assessment

Once a patient has an idea of which modalities s/he may want to do—and why—a clinician needs to determine whether the patient can physically or emotionally do those options. In a prospective study evaluating 1,303 CKD stage 3–5 patients, approximately 13% could not do PD for physical reasons, while 2% could not do HD, and 46% would not qualify for a transplant. (Mendelssohn DC et al, 2009). If a patient is not physically suited to a desired modality, this needs to be explained, and a next-best choice made.

Step 3: Modality Education

Having been vetted as suitable for a modality of choice, the patient and partner (if there is one) would now benefit from education to learn the details about how the treatment works and what tasks are associated with it. Patients who know which options they are considering—and why—may be more likely to participate in education, ask questions, and reach a decision.

Step 4: Make a Treatment Choice and Set Up Training

The patient can talk with the patient or nurse about a final decision, which will be noted in the medical record, and a training slot can be reserved. If the patient requires access placement, get appropriate referrals started. Tell the patient what training hours and days to expect and send them to websites, message boards, online support groups, or other resources to help get them started. Some patients will be interested in receiving the training manual for the machine they will use.

Look to Other Countries as Models. In the U.S., when patients choose PD or home HD, the Medicare 2728 form does not have a field for presence of a care partner, so these data are not tracked in the United States Renal Data System. However, the U.S. clinic model seems to assume the presence of a highly-involved “caregiver” for home HD.

In fact, a report from a 2018 National Kidney Foundation-Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-KDOQI):

A care partner’s role, which is vital to the success of a home dialysis patient, is a significant commitment. Care partner concerns can become unmanageable and cause burnout. Stress, burnout, isolation and lack of support are part of care partner concerns.

Contrast that perspective with a paper from Australia/New Zealand (ANZ) (Agar JWM, 2008):

“In ANZ, home HD is most commonly patient-delivered. A “partner” may or may not be trained—fully, in part, or at all—and even if trained, may or may not be present during the dialysis. Rarely is the partner, if present, required to take a primary role in the dialysis. By relieving the carer—who may also fulfill a breadwinner role—of the primary responsibilities for home HD and ensuring the patient takes the primary dialysis role, carer fatigue is minimized.”

Various countries approach the role of the patient vs. the care partner very differently:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved solo home HD during the day using a NxStage machine in August, 2017. (NxStage, 2017). After several years, dialysis providers wrote Policies and Procedures to cover this new option, yet even today, this option is underutilized and some clinics or provider companies do not offer it. Deliberately not burdening care partners by putting the onus of home treatment on them is a strategy that deserves attention as a way to reduce home HD dropout.

CMS Never Defines the Care Partner Role While Medicare requires a partner for patients who do home HD at night or during the day with machines other than NxStage, the role of care partner was left undefined in the Conditions for Coverage for Dialysis Facilities (Conditions for Coverage, 2008). Without a definition of what a care partner must do, the job of sorting out who will do which of the tasks associated with home HD is left to each patient and care partner to negotiate for themselves—and renegotiate as needed when circumstances change over time.

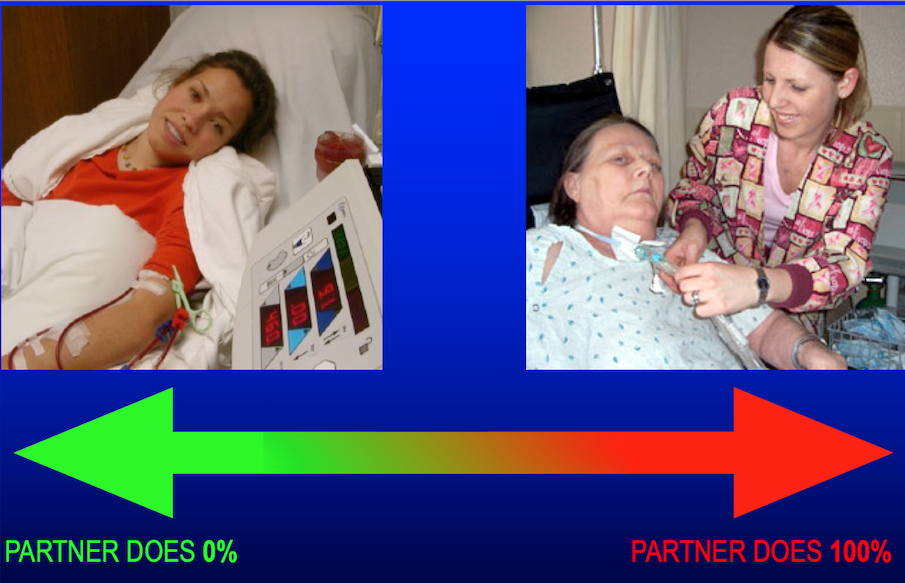

There is a Continuum of Care for Care Partners

In the real world, in people’s homes, a care partner may do zero of the home HD tasks (for a solo or profoundly independent patient) to 100% of them (for a profoundly impaired patient). This means it is important to determine—up front and after training is completed and any time there is a change in health or life status for the patient or the care partner—who will do what.

Plan to Assess Tasks for Home Dialysis (PATH-D)

PATH-Ds for PD and home HD were designed by the Medical Education Institute to be used by a patient and a care partner. Print two copies and give the one-page form to each person, then compare the results to see if they are, literally, on the same page. If not, suggest that they negotiate and observe how they communicate as they do so. You can use this tool before training, at the start of training, at the end of training, any time there is a status change, and/or annually.

Bullying, manipulating, or disrespecting a partner are red flags for dropout, as is when one partner answers for or babies the other. If you see these behaviors, you may need to say, “That sounds like unkind speech, and I wouldn’t want someone to talk to me that way.” Or, “I need to hear from your partner in his own words.” If necessary, call an interdisciplinary team meeting to discuss concerns about safety, domestic violence, or a need for therapy. To succeed, a patient with a troublesome or irresponsible partner may need to do solo dialysis or find a friend to be a care partner.

Severe or unsanitary hoarding of trash and/or animals is an absolute contraindication to home dialysis until the home is cleaned.

Plastic tray tables that can be taken down after treatment and cleaned with bleach wipes can be a solution for cluttering hoarders in otherwise safe homes. Supplies can be kept in plastic tote boxes if a home has signs of animal or insect activity. Any boxes that have signs of being chewed must be discarded, even if the supplies inside appear to be intact. Patients may require a more frequent delivery schedule to allow them time to move the supplies out of the boxes and into containers.

Think about the patient’s home from the perspective of an emergency responder. Can you find the house easily and could a gurney be brought in and moved out? Where are the exits in relation to the treatment area?

Determine whether the water in the home is public or a private well, and if the home is connected to city sewer or has a septic system. In addition, where are the bathrooms and sinks vs. the dialysis space, stairs, etc.? Does the water turn on, is there water pressure, and do the toilets operate? Can patients wash their hands and get back to the treatment area without touching anything? For example, an upstairs sink and a downstairs treatment room is a risk factor for peritonitis or other infection unless the patient uses paper towels to avoid contamination or alcohol-based hand sanitizer immediately before treatment.

Evaluate the electrical system. Watch out for frayed electrical wires or too many extension cords to an outlet. Are there smoke alarms? Reliable power? Most fire departments will give out free smoke detectors to low-income people, and these may also monitor for carbon monoxide. Equipment manufacturers have specifications for machines; they may require grounded, 3-prong outlets or large appliance 50-amp outlets. Your clinic should provide you with a meter to determine if outlets are grounded. Note the presence of a generator.

Assess for fall risks in the home. Could any of the patient’s medications cause dizziness or increase the risk of a fall? Are floor rugs, cords, drain lines or pipes, or belongings on the floor tripping hazards? Can the patient get around the home safely? Water lines and electrical lines that will be used with the equipment must reach the dialysis space—without becoming a fall hazard. If a patient owns a home, PVC conduit pipe can be used to shorten the distance between wires or pipes and the treatment room. Some landlords will permit this as well.

Determine whether the home is heated and cooled so the patient will be comfortable. It is not safe to use an oven or a generator indoors for heat, and space heaters can pose a fire risk and should never be used while anyone is sleeping. Climate change is worsening summer heat: the social worker may know about local programs to help low-income patients obtain air conditioners.

Brainstorm supply storage with the patient. Patients with large homes may have many storage options to choose from. The smaller the space, the more vital it is for patients to make full use of vertical storage (e.g. sturdy shelving units) and storage nooks in dresser drawers, under the dining room table if there is one, under beds, in closets, etc. It saves space to remove fluid bags from boxes and put them into plastic totes. Patients need to understand that they cannot store supplies outdoors or on porches where they could get wet or freeze. Twice-monthly delivery can help PD or home HD succeed for patients whose only hindrance is small homes or apartments.

PD waste is, effectively, urine that can drain into the toilet if the drain line reaches, or be discarded with regular home trash or poured on outdoor plants. The heavy-duty boxes are very difficult for patients to break down, but make excellent, high-quality moving boxes that are always in demand on Next Door and other neighborhood sites. Some patients must pay for garbage collection, and their cost goes up when they have extra trash. Patients who have cars can bring their broken down boxes to the dialysis clinic to discard in the dumpster.

Home HD waste needs to be double-bagged; patients can re-use the bags the lines come in. Sharps must be separately discarded in an approved sharps container that is brought into the clinic when full and exchanged for an empty one. If patients are disturbed about throwing out trash that contains blood, point out that menstrual products are routinely discarded in regular trash. If landlords complain, this same point can be made to them, or reasonable accommodations under the ADA can be mentioned.

Are pets cared for and healthy? Are litter boxes attended to? Home dialysis patients can safely have pets, with precautions to wash hands and avoid letting a pet bite, claw, or pull on the access or treatment tubing. Pets cannot be permitted to lie on top of sterile supplies or warming PD bags. Birds must be kept out of the treatment room entirely, and air filters would be ideal. Fish and reptiles can carry dangerous bacteria; it is safest for patients to wear gloves to handle these pets or clean their enclosures.

Conclusion

As you now know, meeting patient expectations for home dialysis involves ensuring that your patients are selecting modalities that best fit their lives.